UBC researchers believe a group of killer whales observed hunting marine mammals including sperm whales, as well as a sea turtle, in the open ocean off California and Oregon could be a new population.

Based on available evidence, the researchers posit in a new study published in Aquatic Mammals that the 49 orcas could belong to a subpopulation of transient killer whales or a unique oceanic population found in waters off the coast of California and Oregon.

“The open ocean is the largest habitat on our planet, and observations of killer whales in the high seas are rare,” said first author Josh McInnes, a master’s student at the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF). “In this case, we’re beginning to get a sense of killer whale movements in the open ocean and how their ecology and behavior differs from populations inhabiting coastal areas.”

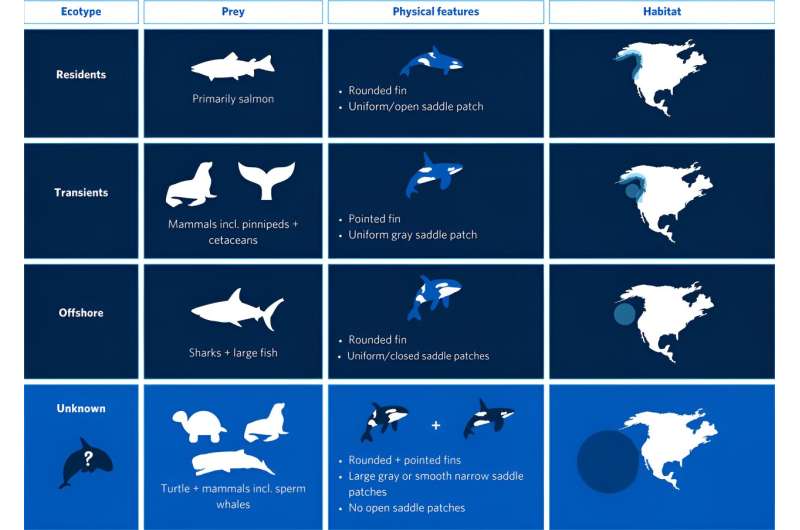

Three ecotypes of killer whales live along the coasts of California and Oregon: ‘residents,’ ‘transients,’ and ‘offshores’.

The unknown orcas have been spotted before, but the new paper contains a weight of evidence gathered from nine encounters with 49 animals from 1997 to 2021, enough to form a solid hypothesis, the researchers said.

“It’s pretty unique to find a new population. It takes a long time to gather photos and observations to recognize that there’s something different about these killer whales,” said co-author Dr. Andrew Trites, IOF professor.

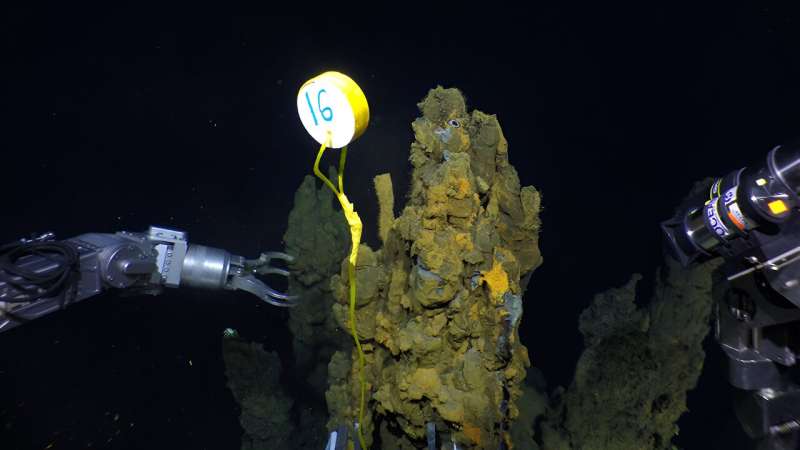

The 49 killer whales could not be matched with any known animals through photos or descriptions. “In one of the first encounters researchers had with a pod of these oceanic killer whales, they were observed taking on a herd of nine adult female sperm whales, eventually making off with one. It is the first time killer whales have been reported to attack sperm whales on the West Coast,” said McInnes.

“Other encounters include an attack on a pygmy sperm whale, predation on a northern elephant seal and Risso’s dolphin, and what appeared to be a post-meal lull after scavenging a leatherback turtle.”

Shark scars provide vital clues

A key clue to the new population’s presumed habitat range lies in cookie-cutter shark bite scars observed on almost all of the orcas. This parasitic shark lives in the open ocean, meaning the new population primarily inhabits deep waters far from land.

The orcas also feature physical differences from the three main ecotypes, including in their dorsal fins and saddle patches—the gray or white patches by the fin.

“While the sizes and shapes of the dorsal fins and saddle patches are similar to transient and offshore ecotypes, the shape of their fins varied, from pointed-like transients to rounded-like offshore killer whales,” said McInnes. “Their saddle patch patterns also differed, with some having large uniformly gray saddle patches and others having smooth narrow saddle patches similar to those seen in killer whales in tropical regions.”

Along with marine mammal stock assessment surveys, fishermen and passengers on an open-ocean birding expedition and whale-watching tour also provided observations of the unidentified killer whales, said Dr. Trites. Spotting the new population has become something of a hobby among fishermen, some of whom have bought cameras for their trips specifically to snap an encounter, the researchers said.

The researchers hope to document more sightings and gather more information, including acoustic data about the orcas’ calls and genetic information from DNA samples to investigate further how these killer whales may differ, or not, from already documented populations.